Tackling drugs or tackling drug policy?

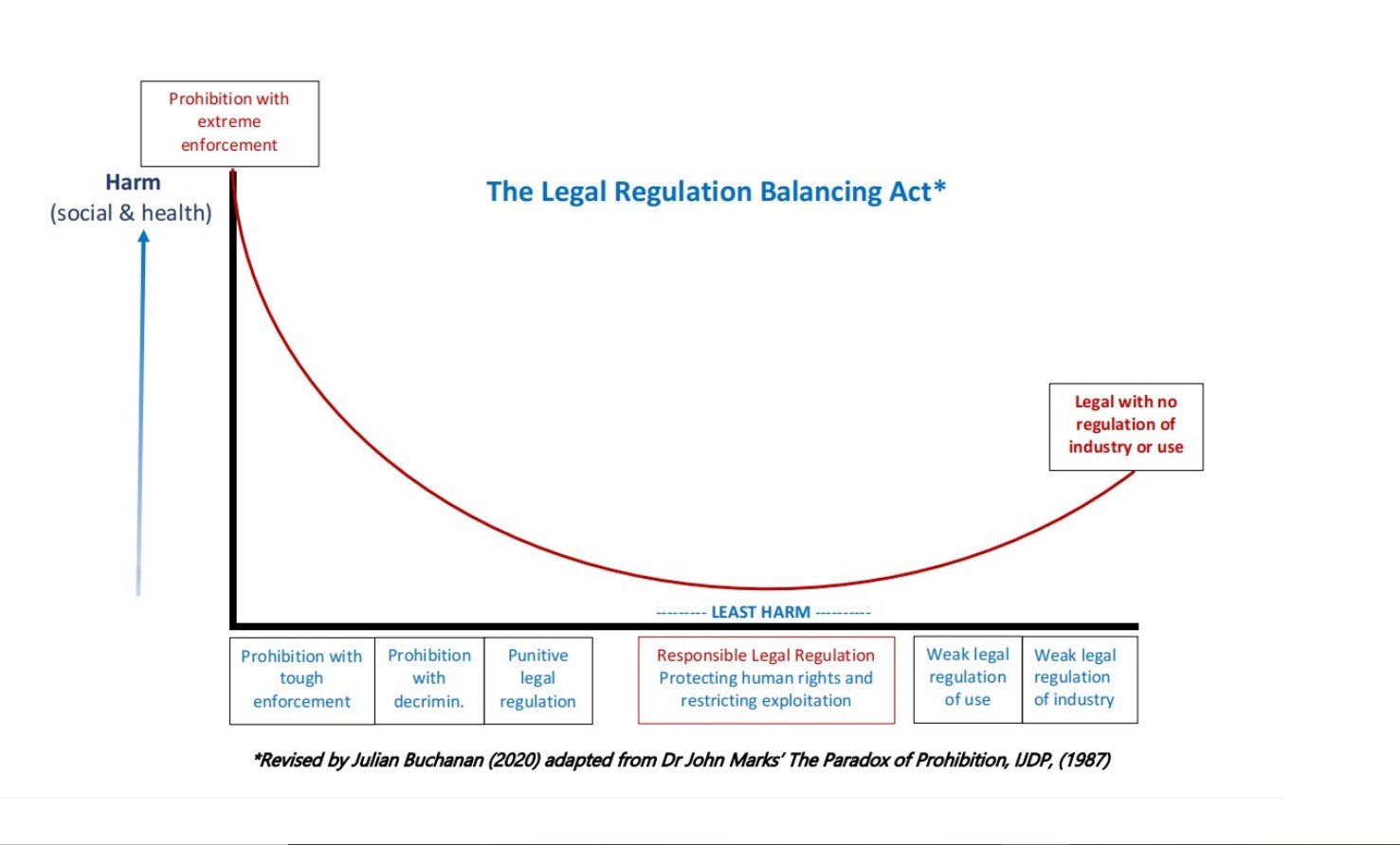

When we discuss legalising drugs, you could be forgiven for imagining that we must be talking about allowing drugs to be introduced and circulated across New Zealand with little oversight, but this view is misguided.

Despite prohibition, drugs are already here, widely circulated, easily available and used across New Zealand with no legal regulatory oversight. In terms of supply and demand it matters little whether they are prohibited or legally regulated. For example, the Dunedin and Christchurch longitudinal study published in 2020 that followed 1000 people from birth into their 40’s, found 80% of kiwis had used cannabis - despite the regime of prohibition, criminalisation and strict law enforcement.

The latest World Drug Report (2023) from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) indicates that despite tough law enforcement, neither the global demand nor global supply of illicit drugs has reduced. In fact, both supply and demand have been steadily increasing for decades under prohibition.

This graph from a USA study published back in 2017 shows cannabis use across European and North American countries. Notice, the two highlighted countries that took a step away from prohibitionist driven policies many decades ago, don’t show excessive cannabis use compared to other countries that strongly enforce prohibition. In 1976 the Netherlands made it legal to sell cannabis in Amsterdam coffee shops, while in 2001 Portugal decriminalised all personal possession of prohibited drugs. Interestingly, levels of injecting drug use in both countries compares favourably with other European countries (EMCDDA 2023).

It is clear that prohibitionist drug policy has no significant impact on levels of drug use. While prohibition has limited control on overall levels of supply or demand, it does however have considerable unintended negative outcomes elsewhere. As a result of driving drugs underground, prohibition also creates enormous additional risks; the person who using drugs:

1. Has no idea of the purity or strength of the drug.

2. Has no idea of the content of the drug — it could contain toxic ingredients that may cause serious harm, even death. It might not even be the drug they thought they purchased.

3. Has to buy drugs ‘underground’ — exposing the person to a potentially dangerous criminal underworld with no consumer protection.

4. Is at risk of acquiring a criminal record for drug possession — which would have lifelong damaging consequences on employment prospects, education, insurance, travel and housing.

5. Because of fear of arrest and punishment drugs are often used in secret. This may mean using alone, in an isolated location which could be potentially dangerous especially — such as a condemned building, under a railway bridge, by a river etc.

6. People who have to hide their use of prohibited drugs are less likely to seek help, support or advice, even when serious issues arise.

7. People with life-limiting medical conditions who can’t afford/can’t access legal medication or who’s condition fails to respond to pharmaceutical medicines but find benefit from a prohibited drug, are placed under considerable strain and pressure trying to self-medicate.

8. Enforcement of drug laws unfairly target poorer people, young people and Māori — further limiting the opportunities for already marginalised people by adding a criminal record.

9. Policing drug use is an expensive waste of police time — time that could be better spent catching criminals and protecting victims from physical/sexual violence, trespass, theft and burglary.

10. The prohibition of drugs fuel an extremely lucrative illegal market where disputes are resolved by violence, disrupting communities and making citizens less safe.

Prohibition was enshrined by the UN Single Convention of Narcotic Drugs in 1961. Like a number of misguided post war policies that evolved in the 1950s - in respect of woman, homosexuality, indigenous people, mental health, abortion, suicide and disabilities - prohibition is a policy based on prejudice, propaganda and misinformation instead of scientific evidence, human rights principles and pragmatism.

Thankfully, most ill-conceived laws adopted in post war New Zealand have long since been challenged and overturned, but drug prohibition enshrined in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 remains firmly in place. Fifty years of harm and failure later, we have an opportunity now to change the law. We know people will use drugs regardless of whether they are legal or prohibited, so pragmatically it makes sense to adopt policies that reduce risks and harms associated with drug use. Responsibly regulating all drugs is one such step.

The legal regulation debate has little to do with the pros and cons of particular drugs – these drugs are already in circulation and being used ‘underground’. Instead of debating drugs, we need to debate the pros and cons of the current system, a system that promotes particular psychoactive substances while prohibiting others. Is the distinction between legal and illegal drugs based on science or evidence? Does prohibition reduce or increase harm for people who use prohibited substances? These are the questions that we should be asking.

It is important therefore that we stop endlessly debating the risks or benefits of particular drugs – because drug use will continue regardless - and spend more time understanding prohibition and its consequences, and considering alternative ways that we can live with, and better manage drugs.

We need to end the harms caused by drug prohibition - responsible legal regulation offers us the best chance to do that, and importantly we need to learn to live with drugs and develop policies that prevent harm. While the entire market remains unregulated, unaccountable, underground and undeclared, the country is also losing millions of dollars in tax revenue and employment opportunities.